L’intervento che segue fa riferimento alla relazione presentata al Parlamento Europeo di Bruxelles da Federica Corrado, responsabile dell’Area ricerca dell’Associazione Dislivelli, durante la Conferenza Finale Europea “Strategies to increase the attractiveness of mountain areas“, relativa al progetto Interreg IV C PADIMA (Politiche contro lo spopolamento nelle aree montane).

La Conferenza è stata organizzata sotto l’alto patronato di Ms Veronica Lope Fontagné, Membro del Parlamento, e vi hanno partecipato parlamentari europei e soggetti europei coinvolti nel progetto. La relatrice ha partecipato su incarico della Provincia di Torino, partner ufficiale del progetto.

What demographic trends have been observed during the last 20 years in the study areas?

The focus of this presentation deals with the recent changes in demographic trends: dimensions, meaning and reasons of the phenomenon.

Actually, many researches (from European Commission documents to Nordregio studies to Alpine Convention Demographic Report, to Massif Central Demographic analysis and so on) underline that in the last period in many European mountain territories demographic trend has become positive. This phenomenon is still limited to specific mountain areas but at the same time it is an important sign that something is changing.

New ideas, new solutions and new activities are proposed by mountain territories. Mountains produce a lot of good practices. Local inhabitants seem to implement development paths conscious of the potential of their territories.

Because of this, another image – that is different from the past – of the “mountaineer” has been created.

What is happening?

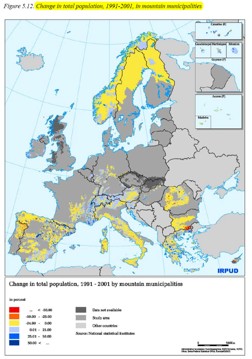

Until last century mountain territories was a places of emigration from the North to the South of Europe (Fig. 1-2). In fact, observing the situation around the last fifty-sixty years in PADIMA study areas, it emerges that:

- mountain region of Buskerud has had a population decline over the last ten years. The four municipalities with the greatest decline also have the largest average birth deficit;

- In Hedmark all the mountain municipalities have suffered from depopulation during the last sixty years (except Tynset) for two reasons: birth deficit and negative migration rate;

- rural municipalities in Dalarna County have decreased a lot during the last 60 years (around 25% of population);

- Massif Central saw a strong decrease in population until the end of the last century;

- the Province of Teruel has lost 42% of its population in the last 50 year;

- Western Italian Alps (Susa and Chisone Valley in Piedmont Region and Brembana Valley in Lombardy Region) registered a long decline and negative demographic trends.

Fig. 1 Padima project partners: Buskerud County (Norway), Hedmark County (Norway), Dalarna County (Sweden), UCCIMAC (France), ERSAF-Lombardy Region (Italy), Province of Turin (Italy), Province of Teruel (Spain, lead partner), Euromontana (Belgium, coordinator)

Fig. 2 Change in total population 1991-2001 by mountain municipalities (ESPON source)

This negative image of the mountain territories seems to change, first of all in visible territorial transformation: from the requalification of old villages to the creation of technologic refuges and so on.

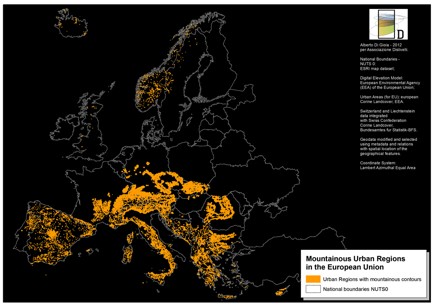

To describe this phenomenon, we should recognize that important differences exist among European mountain areas in terms of natural environment, morphology and population density (Fig. 3). Norway and Sweden there are low density population areas with small villages that still carry the necessary infrastructure. In Alpine area, for example, there are many small and medium cities that function as central regions. The same situation is in Massif Central. In Spain we have very low density areas and an internal urban core region on which mountain people gravitate.

Fig. 3 Mountainous Urban Regions in the European Union

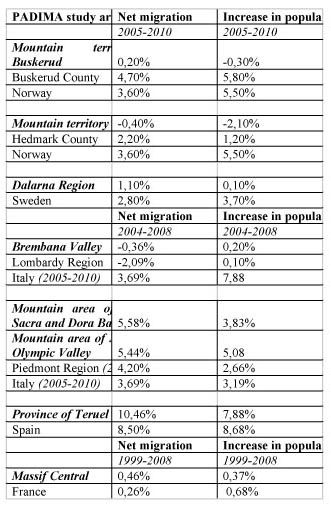

Taking into account territorial differences, we could observe recent demographic trends in PADIMAstudy areas (Tab. 1). In general in almost all PADIMA study areas demographic trends have become positive, except for Buskerud and Hedmark.

The data of net migration is generally bigger than the data of increase population (except for Brembana Valley). This data outlines that the phenomenon of repopulation is linked to immigration processes and not to birth increases.

In Italian Olimpic Valley and Spanish mountain research areas the value of net migration exceeds the national value: This is an interesting piece of information that in Mediterranean areas people decide to move to the mountains from other territories (lowlands specially).

In Buskerud the data of increase population is now negative, but it registers a positive value for immigration. In Hedmark the data of immigration doesn’t become positive but it reveals a situation of immigration better than the birth-death deficit.

Table 1: Recent demographic changes in PADIMA study areas

On this framework, it is possible to affirm that the process of repopulation of European mountain territories is linked to new inhabitants. These new inhabitants invest in their new life and surroundings, they become “care takers” of the mountains and guardians of the socio and territorial biodiversity .

To understand the territorial aspects of this phenomenon, it is necessary “to go deeper into the data”, modifying the focal distance to a more localized area.

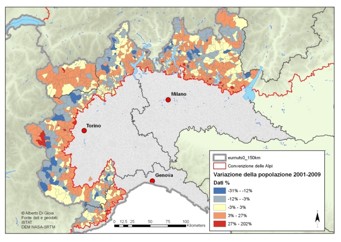

According to this idea, the example of Susa Valley, study area of PADIMA project in Province of TURIN, Piedmont Region,Italy.

In Table 1 Susa Valley has shown a positive demographic trend. In the map of demographic changes at municipalities level, it emerges that the general positive value is very different in the whole territory. We have important increase in population in high valley, dedicated to tourism sector, and in the low part of the valley, that is chosen by a lot of alpine commuters, people who live in rural context but work in Turin metropolitan area. Serious problems of depopulation regard the middle part of the valley where there are few territorial services, where there isn’t an economic developed sector. But at the same time middle valley has been less urbanized than the other parts of the valley, so it has a potential in terms of environment, culture and so on to put in value.

Fig. 4 – Demographic changes (2001-2009) in Susa Valley

This example puts in evidence that the increase in population is linked to the existence of different territorial concentration of migrations. Referring to this we can propose different typologies of new inhabitants directly correlated to their daily movement, job, life style.

These typologies are:

1. permanent inhabitants

- mountain peri-urban migrants , that identify commuters, subjects who live in rural context but work in low land cities

- returnees, people who come back for emotional reasons or for origin in a mountain place

- creative class, that includes artists, software developers, and so on..it is a particular group of people “bringer” of new projectualities. The importance of this typology is recognized also by OECD who defines these people as creators of innovative activities in mountain areas.

- immigrants for condition, generally people who came from extra-European countries or from countries just entered in European Union, especially from East part of Europe.

- neo-rural, people of different ages with a specific ideology of wilderness, or strong contact with nature

2. temporary inhabitants

- multi-local dwellers, a typology presented in many mountain territories and refers to people that stay in the mountains for long period of time but stay for the rest of the year in another territorial context

- seasonal workers, second homes inhabitants, people who stay for job or leisure in mountain territories during holidays period.

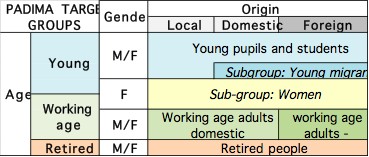

In general, PADIMA project proposes a table in which mountain inhabitants are distinguished by age-gender-origin and it is possible to recognize that new inhabitants correspond to:

- young pupils and students that move to the mountain with their families

- working age adults (women and men)

- retired people

Tab. 2 – PADIMA project classification of new inhabitants referring to age, gender, origin.

The reasons to move in the mountains are:

- Quality of life

- Natural environment

- Job opportunities

- Low cost of life

- Close to family and friends

Nevertheless there are some reasons to move out:

- Nevertheless there are some reasons to move out

- lack of access to services

- long distances to work and to services

- lack of cultural activities

- too small communities (too “transparent” society)

- harsh climatic conditions

- search for better or more diversified job opportunities

In conclusion PADIMA project has shown that new inhabitants represent the occasion and the opportunity to face the traditional challenges in mountain areas in order to solve them in an innovative way.

Federica Corrado